Mansudae Master Class: The Monumental Gifts from Africa

Since 1970, the North Korean government has constructed many buildings, monuments, and statues in Africa. These architectural structures have been covered by the international press since 2010, when the African Renaissance Monument was inaugurated in Senegal. I began intensive research on the subject in 2012 for a documentary film that is focused, in particular, on the buildings made by the North Koreans, free of charge, in Africa in the 1970s. For this project, I interviewed African journalists, museum directors, architects, and others interested in North Korean arts and architecture. None of the people I spoke to know exactly why the North Koreans offered their help at no cost. They assume, however, that among the main reasons is the friendship between African leaders/dictators and Kim Il-sung, the first North Korean leader/dictator.

To date, the North Koreans have constructed buildings, monuments, and statues in eighteen African countries, roughly half of which received the free-construction benefits offered by Kim Il-sung. Behind this North Korean diplomatic strategy lies a competition between North and South Korea, something not generally known in either the Western world or Africa. Just after the armistice at the end of the Korean War in 1953, problems related to the military demarcation line between North and South Korea and to the stationing of the U.S. Army in South Korea were addressed but not resolved by the United Nations—and then magnified by the Cold War and the larger world conflict between democracy and communism.

It is within this context, as the newly independent African nations joined the United Nations in the 1960s, that North Korea first sought to secure African support. In addition, North Korea strove to join the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) of which many African countries were members.(1) The numerous architectural structures built across Africa in the 1970s—including the Youth and Children’s Palace in Sudan, the stadium in Tanzania (called the Kim Il-sung Stadium), the presidential palace in Madagascar, and the water channels for agriculture in Ethiopia—are regarded as examples of North Korea’s diplomatic efforts.

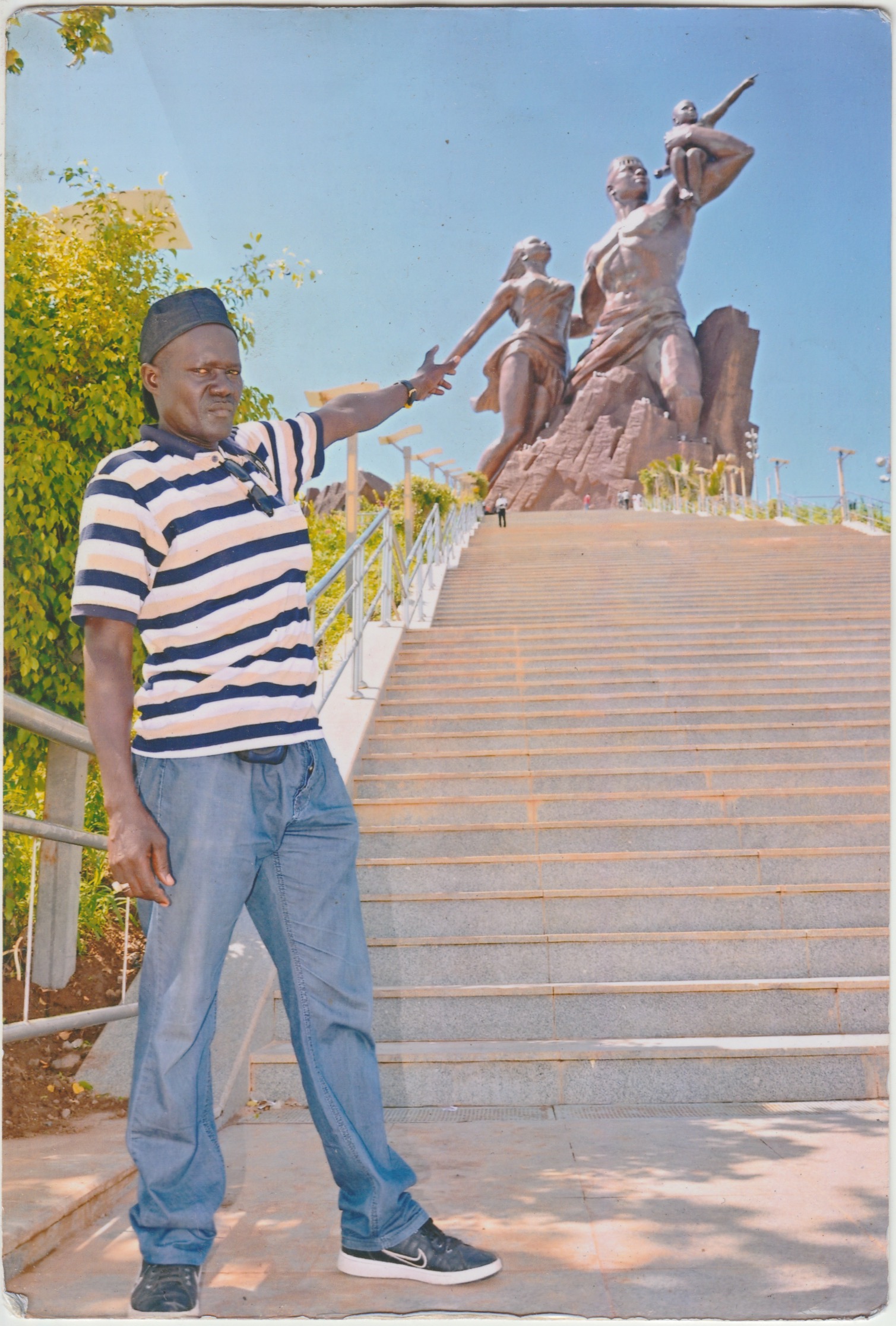

The situation has, ironically, changed since the 2000s. As the economic situation in North Korea grew dramatically worse in the mid-1990s, the country’s Mansudae Overseas Project Group of Companies began to dispatch artists and laborers to Africa.(2) During long-term stays in Namibia, Senegal, Botswana, Congo, etc., members of this organization have earned foreign currency by constructing large-scale statues and buildings. In fact, these structures reflect the well-made forms of the Socialist Realism style; for example, the new Independence Memorial Museum, opened in Namibia in 2014, features the strong vertical lines and symmetrical surface characteristic of the Socialist Realism style, as does the Youth Hotel in Pyongyang, North Korea. The large African Renaissance Monument showcases North Korea’s current bronze-casting technique, which has been used and developed to make more than twenty thousand statues of Kim Il-sung. However, the buildings and the monuments made by the North Koreans inevitably become subject to debate for political and social reasons: because they sometimes honor the dictatorships of African nations, they arouse suspicion of hidden connections between North Korea and Africa—the latter of which possesses the main materials necessary for nuclear development.

Architectural structures can be seen as controversial in any city. If perceived as overtly social and/or political, they can become subject to criticism and gossip. Today, North Korea is ridiculed, yet at the same time, it has captured the world's attention. Human rights violations and the political situation in North Korea have clouded how these structures are viewed. In this context, North Korean architecture, monuments, and statues in Africa could serve as a portal to greater understanding, for they represent not just Africa, but also the history of the Korean peninsula and the current state of North Korea.

1) In Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955, there was a meeting among newly independent nations of Asia and Africa for anti-imperialism, independence, and non-alliance against more powerful Western nations. The first Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) Summit Conference took place in Belgrade in 1961; after the second meeting, African countries made up the majority of the group.

2) Known as the cradle of revolutionary art, the Mansudae Art Studio is a North Korean arts organization, established in 1959. Its members have built about 3,8000 statues and 179 monuments throughout North Korea. Mansudae Overseas Project Group of Companies and its affiliated departments are in charge of buildings, monuments, and other architectural projects overseas. This department is known for earning substantial foreign currency since 2000.

Since 1970, the North Korean government has constructed many buildings, monuments, and statues in Africa. These architectural structures have been covered by the international press since 2010, when the African Renaissance Monument was inaugurated in Senegal. I began intensive research on the subject in 2012 for a documentary film that is focused, in particular, on the buildings made by the North Koreans, free of charge, in Africa in the 1970s. For this project, I interviewed African journalists, museum directors, architects, and others interested in North Korean arts and architecture. None of the people I spoke to know exactly why the North Koreans offered their help at no cost. They assume, however, that among the main reasons is the friendship between African leaders/dictators and Kim Il-sung, the first North Korean leader/dictator.

To date, the North Koreans have constructed buildings, monuments, and statues in eighteen African countries, roughly half of which received the free-construction benefits offered by Kim Il-sung. Behind this North Korean diplomatic strategy lies a competition between North and South Korea, something not generally known in either the Western world or Africa. Just after the armistice at the end of the Korean War in 1953, problems related to the military demarcation line between North and South Korea and to the stationing of the U.S. Army in South Korea were addressed but not resolved by the United Nations—and then magnified by the Cold War and the larger world conflict between democracy and communism.

It is within this context, as the newly independent African nations joined the United Nations in the 1960s, that North Korea first sought to secure African support. In addition, North Korea strove to join the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) of which many African countries were members.(1) The numerous architectural structures built across Africa in the 1970s—including the Youth and Children’s Palace in Sudan, the stadium in Tanzania (called the Kim Il-sung Stadium), the presidential palace in Madagascar, and the water channels for agriculture in Ethiopia—are regarded as examples of North Korea’s diplomatic efforts.

The situation has, ironically, changed since the 2000s. As the economic situation in North Korea grew dramatically worse in the mid-1990s, the country’s Mansudae Overseas Project Group of Companies began to dispatch artists and laborers to Africa.(2) During long-term stays in Namibia, Senegal, Botswana, Congo, etc., members of this organization have earned foreign currency by constructing large-scale statues and buildings. In fact, these structures reflect the well-made forms of the Socialist Realism style; for example, the new Independence Memorial Museum, opened in Namibia in 2014, features the strong vertical lines and symmetrical surface characteristic of the Socialist Realism style, as does the Youth Hotel in Pyongyang, North Korea. The large African Renaissance Monument showcases North Korea’s current bronze-casting technique, which has been used and developed to make more than twenty thousand statues of Kim Il-sung. However, the buildings and the monuments made by the North Koreans inevitably become subject to debate for political and social reasons: because they sometimes honor the dictatorships of African nations, they arouse suspicion of hidden connections between North Korea and Africa—the latter of which possesses the main materials necessary for nuclear development.

Architectural structures can be seen as controversial in any city. If perceived as overtly social and/or political, they can become subject to criticism and gossip. Today, North Korea is ridiculed, yet at the same time, it has captured the world's attention. Human rights violations and the political situation in North Korea have clouded how these structures are viewed. In this context, North Korean architecture, monuments, and statues in Africa could serve as a portal to greater understanding, for they represent not just Africa, but also the history of the Korean peninsula and the current state of North Korea.

1) In Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955, there was a meeting among newly independent nations of Asia and Africa for anti-imperialism, independence, and non-alliance against more powerful Western nations. The first Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) Summit Conference took place in Belgrade in 1961; after the second meeting, African countries made up the majority of the group.

2) Known as the cradle of revolutionary art, the Mansudae Art Studio is a North Korean arts organization, established in 1959. Its members have built about 3,8000 statues and 179 monuments throughout North Korea. Mansudae Overseas Project Group of Companies and its affiliated departments are in charge of buildings, monuments, and other architectural projects overseas. This department is known for earning substantial foreign currency since 2000.